When the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible and we had the land. They said, “Let us pray.” We closed our eyes. When we opened them, we had the Bible and they had the land. ~ Kenya’s post-colonial Father: Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, Prime Minister of Kenya (1963-64), President (1964-78), and author of “Facing Mount Kenya.” These words are sometimes attributed to South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu (Winner: Nobel Peace Prize, 1984; Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism, 1986; Pacem in Terris Award, 1987; Sydney Peace Prize, 1999; Gandhi Peace Prize, 2005; and Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2009).

When the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible and we had the land. They said, “Let us pray.” We closed our eyes. When we opened them, we had the Bible and they had the land. ~ Kenya’s post-colonial Father: Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, Prime Minister of Kenya (1963-64), President (1964-78), and author of “Facing Mount Kenya.” These words are sometimes attributed to South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu (Winner: Nobel Peace Prize, 1984; Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism, 1986; Pacem in Terris Award, 1987; Sydney Peace Prize, 1999; Gandhi Peace Prize, 2005; and Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2009).

James Bonnet’s insights on the creation of the “old great stories” brought Mzee Kenyatta’s quote home to me in an interesting light, particularly with regard to the consequences of writing as a communication technology and dissemination tool. I grew up with the Bible and history – “irrefutably” documented in the texts before me – being collectively packaged as proof of western superiority. That African images such as those of Horus (Heru in Kemet/ancient Egypt) and Isis (Auset) may have been co-opted in this grand enterprise is not of so much concern as the subsequent dissemination of a single story that did not acknowledge my agency except as a colonized subject on its peripheral margins. The abstract writing technology through which this story was programmed reinforced its own problematic tendencies toward literal interpretation.

James Bonnet’s insights on the creation of the “old great stories” brought Mzee Kenyatta’s quote home to me in an interesting light, particularly with regard to the consequences of writing as a communication technology and dissemination tool. I grew up with the Bible and history – “irrefutably” documented in the texts before me – being collectively packaged as proof of western superiority. That African images such as those of Horus (Heru in Kemet/ancient Egypt) and Isis (Auset) may have been co-opted in this grand enterprise is not of so much concern as the subsequent dissemination of a single story that did not acknowledge my agency except as a colonized subject on its peripheral margins. The abstract writing technology through which this story was programmed reinforced its own problematic tendencies toward literal interpretation.

Joseph Campbell has identified this communication-issue as a problem of reading words in terms of prose rather than poetry. His hero’s journey motif reads story connotatively rather than denotatively, so as to discover and recognize the metaphor that is intended to point the way to one’s true and fullest nature. Coinciding with Carl Jung’s process of individuation, this motif of transcendence finds universality in its focus on the journey inward… on mysteries that were/are the focus of ancient Egyptian religion and hieroglyphic symbols. And in this sense it is interesting that, as James Bonnet explains, it was oral tradition – the living word (ref: Nommo) – that maintained the inner roadmaps and hidden wisdom even as the legends evolved with a variety of outward forms, plot twists and foreign names across cultures and over time.

Auset-Hathor’s sacred sycamore tree enshrined in Mataria (a Cairo suburb) is now a Christian pilgrimage site for thousands who believe it gave the Holy Family shelter during their Egyptian sojourn. One might argue that the more recent consecrating of this tree to the Holy Virgin Mary illustrates Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’s point about the colonizing process… the renaming of African landmarks as a mode of possession and emblem of dominance by outsiders with their own justifications and religious and/or political iconography. Another of many examples in Africa: “Lake Victoria,” the source of the Nile – from which much of ancient Egyptian livelihood, sacred wisdom, and contributions to world civilizations came – is still named for the British Queen who presided (1837-1901) over her country’s role in occupying and obtaining African land and treasure.

Auset-Hathor’s sacred sycamore tree enshrined in Mataria (a Cairo suburb) is now a Christian pilgrimage site for thousands who believe it gave the Holy Family shelter during their Egyptian sojourn. One might argue that the more recent consecrating of this tree to the Holy Virgin Mary illustrates Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’s point about the colonizing process… the renaming of African landmarks as a mode of possession and emblem of dominance by outsiders with their own justifications and religious and/or political iconography. Another of many examples in Africa: “Lake Victoria,” the source of the Nile – from which much of ancient Egyptian livelihood, sacred wisdom, and contributions to world civilizations came – is still named for the British Queen who presided (1837-1901) over her country’s role in occupying and obtaining African land and treasure.

This text was intended to take away my symbols and resources of nature, story, and dreaming… with the support of a curriculum that kept me focused on external forms and literal interpretations of “European superiority” vs “African inferiority and (therefore) need for conversion” from various sanctimonious colonial agents. So I now find myself thinking back with a sense of irony and gratitude to my high-school English teacher who, with an almost discernible wink, would insist in her gravelly voice as I made my way through William Shakespeare, Bertolt Brecht, Graham Greene (et al) that I “read between the lines!” And so I do, in order to rediscover and rekindle my talking drum at the matriarchal and ancestral axis mundi… the organic place from whence the oral-aesthetic derives its human-centered meaning.

This text was intended to take away my symbols and resources of nature, story, and dreaming… with the support of a curriculum that kept me focused on external forms and literal interpretations of “European superiority” vs “African inferiority and (therefore) need for conversion” from various sanctimonious colonial agents. So I now find myself thinking back with a sense of irony and gratitude to my high-school English teacher who, with an almost discernible wink, would insist in her gravelly voice as I made my way through William Shakespeare, Bertolt Brecht, Graham Greene (et al) that I “read between the lines!” And so I do, in order to rediscover and rekindle my talking drum at the matriarchal and ancestral axis mundi… the organic place from whence the oral-aesthetic derives its human-centered meaning.

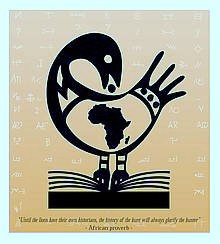

“Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter” ~ African Proverb

The hero’s journey, it seems to me, is ultimately a deeply spiritual one of coming into atonement with Source, and into an understanding of the metaphors of our common humanity that test and potentially enlighten us from their reflections in these outer, material forms (ref: Masquerade motif). Its essence is captured in the African philosophy of ubuntu ~ “I am because we are, and since we are therefore I am.” When our inner eye is opened, the outward material conquests of self-interested agents of any kind who have presumed to shut us out of the place we call “home” while imposing their occupancy and fabricating justifications for their pillage tell a different story…

“Furthermore, we have not even to risk the adventure alone, for the heroes of all time have gone before us. The labyrinth is thoroughly known. We have only to follow the thread of the hero path. And where we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god. And where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves. Where we had thought to travel outward, we will come to the center of our own existence. And where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world.” ~ Joseph Campbell

“Furthermore, we have not even to risk the adventure alone, for the heroes of all time have gone before us. The labyrinth is thoroughly known. We have only to follow the thread of the hero path. And where we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god. And where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves. Where we had thought to travel outward, we will come to the center of our own existence. And where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world.” ~ Joseph Campbell

“Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! for, behold, the kingdom of God is within you.” ~ Jesus (Luke17:21). “The Kingdom of Heaven is within you; and whosoever shall know him/herself shall find it” ~ ancient Egyptian proverb, inscribed on the walls of the Luxor Temple of Amun~Mut~Montu/Khonsu (ancestral African Holy Trinity).

“Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! for, behold, the kingdom of God is within you.” ~ Jesus (Luke17:21). “The Kingdom of Heaven is within you; and whosoever shall know him/herself shall find it” ~ ancient Egyptian proverb, inscribed on the walls of the Luxor Temple of Amun~Mut~Montu/Khonsu (ancestral African Holy Trinity).

Hotep… Malaika

Malaika Mutere, Ph.D. is author of Towards an Africa-centered and pan-African theory of communication: Ubuntu and the Oral Aesthetic perspective Communicatio 38 (2) 2012: 147-163

Really interesting thanks

Thank you!

Pingback: Proverbs from the Luxor Temple of Amun~Mut~Montu/Khonsu |