“With this breath I thee wed, my true nature… my forever… my being. With this breath I say ‘yes,’ and I embrace that which is real within me ~ All that is great within me; all that is beautiful; all that is self-love and gratitude; all that is divine…” (Dion Mial / Michael Bernard Beckwith – lyrics)

In Africa the word is endowed with the generative potential of a seed through the concept of nommo ~ spirit breathing life into the universe through its audible articulation or call. It is a process that is fundamental to human imagination and being: the masculine/god principle implanting its seed and relying on the collaborative feminine/goddess principle out of which genesis and creation are given life and its divine order. African communication flows ritualize this creative consciousness beginning with the call-response motif whose various forms extend themselves socially, politically, and creatively as reflected in pop music genres.

In Africa the word is endowed with the generative potential of a seed through the concept of nommo ~ spirit breathing life into the universe through its audible articulation or call. It is a process that is fundamental to human imagination and being: the masculine/god principle implanting its seed and relying on the collaborative feminine/goddess principle out of which genesis and creation are given life and its divine order. African communication flows ritualize this creative consciousness beginning with the call-response motif whose various forms extend themselves socially, politically, and creatively as reflected in pop music genres.

Jazz conversations, for instance, reflect the decentralized democratic consensus that Africans would create in situations (e.g. hunting-and-gathering activities of such societies in Africa or whilst working on the slave-master’s fields) where group success is dependent on everyone’s input. In contrast, the black church, where a formal centralized leadership is necessary for group cohesion, developed a leader-chorus form of call-response which is reflected for instance in soul music, a tradition that gives us kings, queens, the godfather, Black Moses, etc. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “Somebody has to preach to the choir, otherwise they might stop singing.”

Jazz conversations, for instance, reflect the decentralized democratic consensus that Africans would create in situations (e.g. hunting-and-gathering activities of such societies in Africa or whilst working on the slave-master’s fields) where group success is dependent on everyone’s input. In contrast, the black church, where a formal centralized leadership is necessary for group cohesion, developed a leader-chorus form of call-response which is reflected for instance in soul music, a tradition that gives us kings, queens, the godfather, Black Moses, etc. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “Somebody has to preach to the choir, otherwise they might stop singing.”

Hip-hop emcees (MC or master of ceremonies – an element derived in part from the Jamaican dance hall) representing the voice of the community, play a significant leadership role because of the platform they’ve often battled others for the right to make it to the mic. The circular arrangement of the cypher into which his nommo (words/seed) are cast during verbal battling sessions is the sacred symbol of the feminine and the communal body. It is out of here that new life emerges in this communal hip-hop re-enactment of creation, seasoning those voices who will go out to critique, battle, exhort, speak truth to power, etc. through provocative words, rhymes and rhythms… generating heat, light, and other energies in the process of keeping things real.

Hip-hop emcees (MC or master of ceremonies – an element derived in part from the Jamaican dance hall) representing the voice of the community, play a significant leadership role because of the platform they’ve often battled others for the right to make it to the mic. The circular arrangement of the cypher into which his nommo (words/seed) are cast during verbal battling sessions is the sacred symbol of the feminine and the communal body. It is out of here that new life emerges in this communal hip-hop re-enactment of creation, seasoning those voices who will go out to critique, battle, exhort, speak truth to power, etc. through provocative words, rhymes and rhythms… generating heat, light, and other energies in the process of keeping things real.

As custodians of communal nommo, the emcee follows in the distinguished tradition of the African griot who often serves as a historian, providing musical recitations of significant events he has committed to memory of his people’s past and its unfolding story. The griot may serve at the chief’s side during trials and deliberations, thus also becoming a witness, genealogist, advisor, spokesperson, commentator, diplomat, mediator, interpreter, teacher, exhorter, poet or praise-singer as needed. Often accompanying his recitation through performance on a musical instrument, the griot provides illumination of the present through applicable recall and effective word-smithing. He thus becomes the community’s library, consciousness, and voice or talking drum.

As custodians of communal nommo, the emcee follows in the distinguished tradition of the African griot who often serves as a historian, providing musical recitations of significant events he has committed to memory of his people’s past and its unfolding story. The griot may serve at the chief’s side during trials and deliberations, thus also becoming a witness, genealogist, advisor, spokesperson, commentator, diplomat, mediator, interpreter, teacher, exhorter, poet or praise-singer as needed. Often accompanying his recitation through performance on a musical instrument, the griot provides illumination of the present through applicable recall and effective word-smithing. He thus becomes the community’s library, consciousness, and voice or talking drum.

The African masquerade tradition, an ingenious performance of metaphor in the public space, has taken many forms in Diasporan communities, oftentimes as a strategy for survival. Enslaved Africans mastered different techniques of developing outward forms (masks) that appeased adversarial forces while maintaining the deeper integrity of cultural traditions. The African mask was never created to be commoditized for the European gaze, but rather to be performed as a means of community edification, unification, and survival. During slavery for instance, communication was coded (masked) in spirituals and songs – such as “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” “Steal Away to Jesus,” and “Wade in the Water” – to disguise plans for escape.

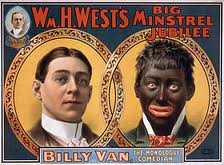

The pop music industry began as a showcase of the white gaze in its belittlement of African oral-aesthetic expression. White actors masquerading in blackface would perform caricatures that lampooned the music and dance they’d appropriated from enslaved African culture.

The pop music industry began as a showcase of the white gaze in its belittlement of African oral-aesthetic expression. White actors masquerading in blackface would perform caricatures that lampooned the music and dance they’d appropriated from enslaved African culture.  Minstrel shows, as the entertainment commodity was known, provided a lens through which many in white audiences the world over consumed demeaning stereotypes of African-American culture beginning in the 1830s.

Minstrel shows, as the entertainment commodity was known, provided a lens through which many in white audiences the world over consumed demeaning stereotypes of African-American culture beginning in the 1830s.

Time after time white appropriation and industry control has compromised the integrity of African cultural expression and its communal role, appropriating and commoditizing it as mere “entertainment,” and then transporting it as such for mainstream consumption. The industry environment cultivated by this masquerade between two culturally adversarial forces presents optimal circumstances within which Trickster deities might intervene, often employing all the tools of the griot’s emcee trade.

Time after time white appropriation and industry control has compromised the integrity of African cultural expression and its communal role, appropriating and commoditizing it as mere “entertainment,” and then transporting it as such for mainstream consumption. The industry environment cultivated by this masquerade between two culturally adversarial forces presents optimal circumstances within which Trickster deities might intervene, often employing all the tools of the griot’s emcee trade.

Natural enemies of the status quo, Trickster deities generally break the rules, sometimes maliciously, but ultimately to bring about healthy change and transformation. Hip-hop culture provides abundant evidence of the problems fostered when the griot’s community-conscious voice is co-opted by the unhealthy fixation of the “status quo” (white control) on promoting messages of violence, sex, drugs, and misogyny through black artists. In a distressing sense it is another form of black-faced minstrelsy when controlling the messengers and the message, ultimately compromising the integrity of a cultural brand and generating real world consequences.

As in the days of slavery, the hip-hop masquerade takes place on the level of street-coded messages and tags representing attitude, e.g. gangsta (“Dogg”) or Rasta (“Lion”), etc. The rap performance nevertheless is intended to be a cultural version of news media, or “black America’s CNN” as Chuck-D famously noted. A number of artists have critiqued the fall of Afrocentric rap to the dehumanizing, commoditizing, and disenfranchizing forces of the adversary:

…the chick was creative

…the chick was creative

But once the man got to her, he altered the native

Told her if she got an image and a gimmick

That she could make money… she did it like a dummy

Now I see her in commercials, she’s universal

She used to only swing it with the inner-city circle

Now she be in the burbs lookin’ rock and dressin’ hip… (from “I Used to Love H.E.R.” by Common)

Epitomized best perhaps by the King of Pop, Michael Jackson, a different kind of Trickster deity emerges out of the Motown model which pedaled fantasy rather than “reality.” During an era of integration and Civil Rights optimism Berry Gordy established his assembly-line formula for success by targeting the mainstream (white) record-buying public with sounds produced from his black-owned and run Motown label. Key to this formula was the creation of a different kind of masquerade: the grooming of African-American artists in Motown’s finishing school and the “sweetening” of their sound to cater to the listening sensibilities of the target constituency.

Epitomized best perhaps by the King of Pop, Michael Jackson, a different kind of Trickster deity emerges out of the Motown model which pedaled fantasy rather than “reality.” During an era of integration and Civil Rights optimism Berry Gordy established his assembly-line formula for success by targeting the mainstream (white) record-buying public with sounds produced from his black-owned and run Motown label. Key to this formula was the creation of a different kind of masquerade: the grooming of African-American artists in Motown’s finishing school and the “sweetening” of their sound to cater to the listening sensibilities of the target constituency.

While Motown may consequently have lost touch with its own community voice, causing latter day scholars such as Nelson George to decry its role in bringing about the death of a cultural language (rhythm and blues), this was nevertheless an ingenious application of the masquerade oral-aesthetic motif which played an important diplomatic role during a pivotal moment in global relations.

In Africa (where Independence was breaking out in conjunction with Civil Rights in the US during Motown’s formative years) the traditional artisan provides the first designation of the mask in constructing and providing its visual symbolism. The dancer who wears it provides the mask its second designation in performance. Without this second designation in the masquerade – the metaphoric human action context – the mask is incomplete and without its deep cultural significance because it has no efficacy as nommo.

In Africa (where Independence was breaking out in conjunction with Civil Rights in the US during Motown’s formative years) the traditional artisan provides the first designation of the mask in constructing and providing its visual symbolism. The dancer who wears it provides the mask its second designation in performance. Without this second designation in the masquerade – the metaphoric human action context – the mask is incomplete and without its deep cultural significance because it has no efficacy as nommo.

Arguably Motown’s most famous initiate, Michael Jackson is the most extreme representation of this masquerade tradition, particularly in his post-Thriller physical evolution. As I’ve written elsewhere, one could reason that in his particular application of the masquerade motif, Jackson himself provided both the first (plastic surgery, skin bleaching, etc.) and the second (performance) designations of the mask. However, the argument follows that the difficulty here for the King of Pop lies in the expectation for his audience to accept his permanent physical transformations as a catalyst for the paradigm shift to the unconditional love, or state of Ubuntu that Michael championed as his mission.

Arguably Motown’s most famous initiate, Michael Jackson is the most extreme representation of this masquerade tradition, particularly in his post-Thriller physical evolution. As I’ve written elsewhere, one could reason that in his particular application of the masquerade motif, Jackson himself provided both the first (plastic surgery, skin bleaching, etc.) and the second (performance) designations of the mask. However, the argument follows that the difficulty here for the King of Pop lies in the expectation for his audience to accept his permanent physical transformations as a catalyst for the paradigm shift to the unconditional love, or state of Ubuntu that Michael championed as his mission.

People of African descent in particular felt increasingly skeptical and betrayed by Michael’s evolving appearance, because it bespoke an “intense self-hatred” and “abnegation of blackness” that has plagued his community of origin since slavery. Some scholars have suggested that this physical metamorphosis was Michael’s attempt to transcend America’s entrenched racial barriers per his lyrics, “It don’t matter if you’re black or white.” Others add that the performativity of Michael’s body further blurred the lines between male/female, child/adult, and even human/animal, thus creating a fictional world of one-ness… of peace and equality through a manufactured hybridity. (Ref: Journal of Pan-African Studies 3 (7), March 2010.)

The dilemma expressed in Michael’s defiant lyrics, “I’m not going to spend my life being a color!” (Black or White) recalls two key notes for me: (1) Berry Gordy’s expressed desire to overcome the stigma of the term “race music” (the prevailing entertainment industry term for black pop music) through his Motown mission; and (2) W.E.B. DuBois’ prescient statement from The Souls of Black Folk:

“Herein lie buried many things which if read with patience may show the strange meaning of being black here in the dawning of the Twentieth Century. This meaning is not without interest to you, Gentle Reader; for the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

“Herein lie buried many things which if read with patience may show the strange meaning of being black here in the dawning of the Twentieth Century. This meaning is not without interest to you, Gentle Reader; for the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

Thus, factoring all these concerns together, one could conclude that the King of Pop indeed became the quintessential 20th century American icon and Trickster deity – both the Man in the Mirror as well as the mirror itself. The mask (his face and skin) is the mirror – reflecting unsettling codes in Michael’s evolving physical make-up that continue to cause personal, social, and academic introspection at the organic and ultimately therapeutic levels intended in a traditional African sense of the masquerade motif. Thus in itself, and when properly looked upon – to borrow from Joseph Campbell (below) – perhaps the performativity of the King of Pop’s post-Thriller body has in fact made a significant contribution to the American social sphere.

“The artist is meant to put the objects of this world together in such a way that through them you will experience that light, that radiance which is the light of our consciousness and which all things both hide and, when properly looked upon, reveal. The hero journey is one of the universal patterns through which that radiance shows brightly.” (from Pathways to Bliss – Joseph Campbell)

“The artist is meant to put the objects of this world together in such a way that through them you will experience that light, that radiance which is the light of our consciousness and which all things both hide and, when properly looked upon, reveal. The hero journey is one of the universal patterns through which that radiance shows brightly.” (from Pathways to Bliss – Joseph Campbell)

![]() Malaika Mutere, Ph.D. is author of Towards an Africa-centered and pan-African theory of communication: Ubuntu and the Oral Aesthetic perspective Communicatio 38 (2) 2012: 147-163

Malaika Mutere, Ph.D. is author of Towards an Africa-centered and pan-African theory of communication: Ubuntu and the Oral Aesthetic perspective Communicatio 38 (2) 2012: 147-163

I was very pleased to find this site. I want to to thank you for your time just for this wonderful read!! I definitely loved every part of it and I have you saved to fav to see new things in your site.

Thanks for stopping by!